|

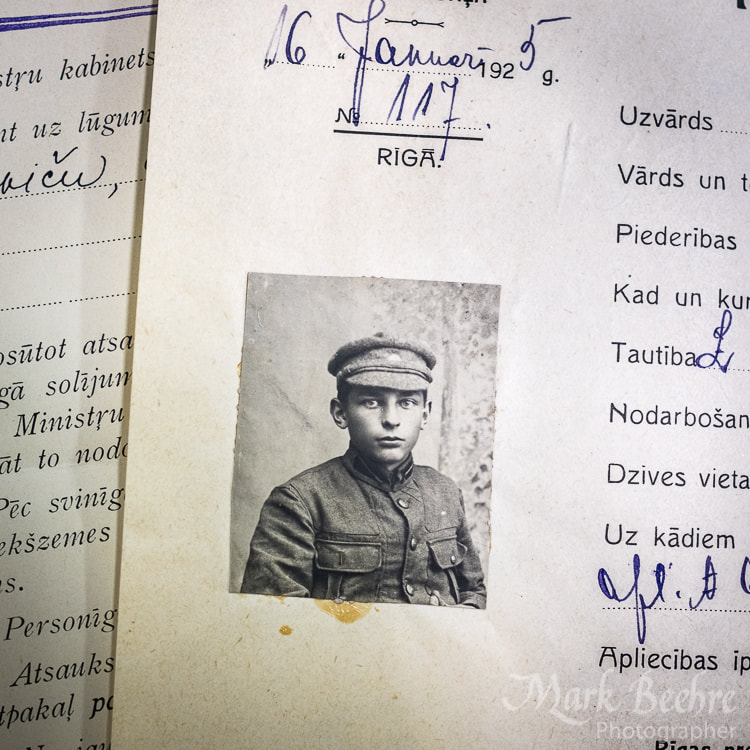

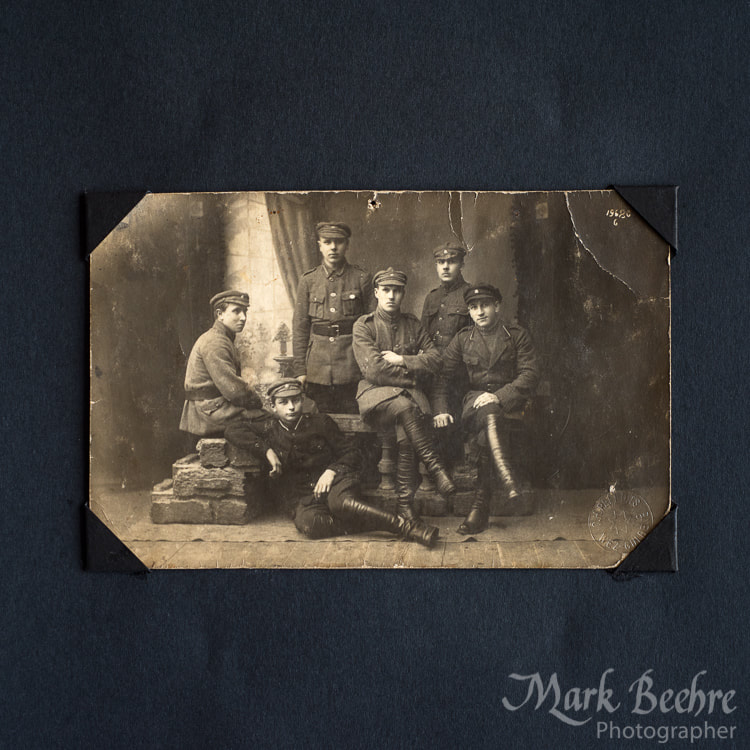

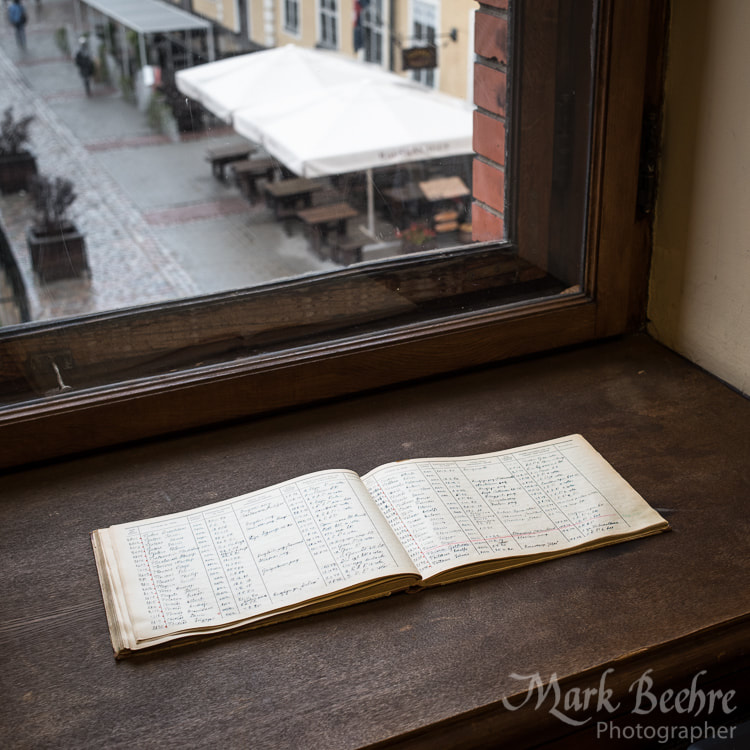

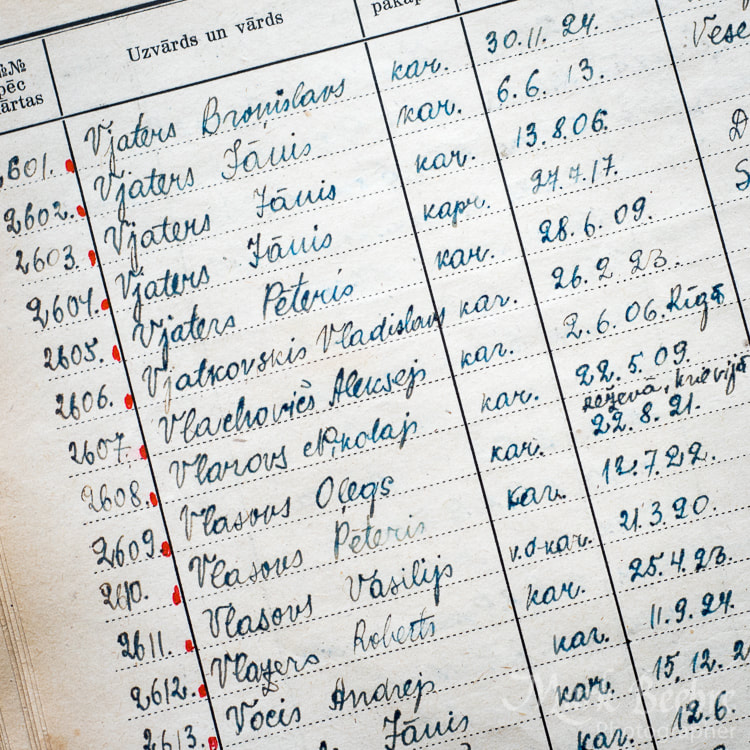

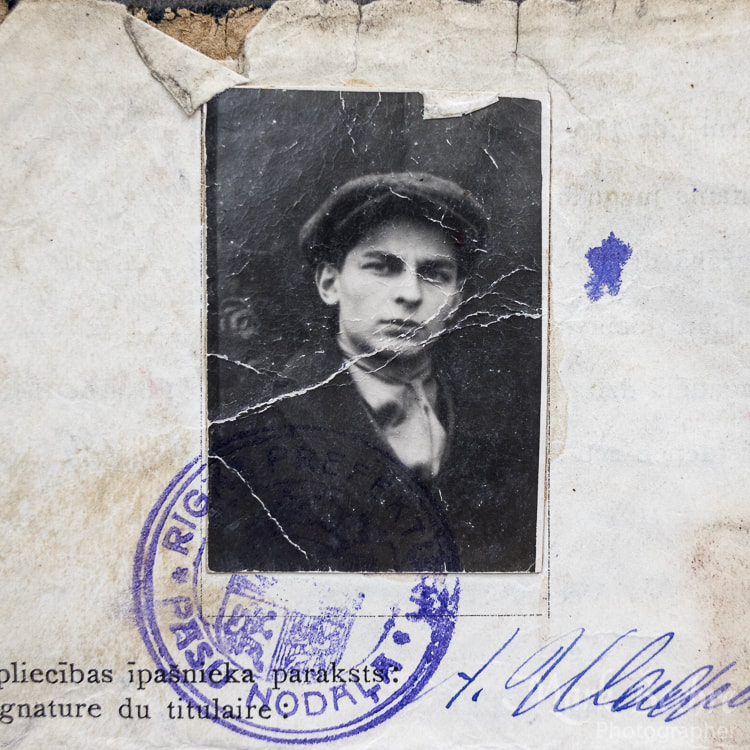

The alarm went at 5.30 this morning, and by 6 R. and I were standing on our deck. The Covid-19 lockdown means that for the first time in more than a hundred years we are unable to gather on ANZAC Day to honour the memories of those who lost their lives in war. Instead, throughout the country, people were invited to stand at their gates, on balconies or decks, or even in their living rooms to listen as the ‘Stand at Dawn’ commemoration was broadcast on national radio. The Last Post played and the Ode – ‘We shall remember them’ – read, we came inside for coffee. The radio stayed on. We heard the stories of some who have been left out of the traditional narratives of heroism and service, such as the ‘native radio operators’ who played vital roles as ‘Coastwatchers’ throughout the Pacific during World War II but were written out of official histories, or the women of the Land Army who kept our farms and our economy running while the men were at war. Listening, I found a photograph of my grandfather, Aleksejs Ulachovičs, and propped it up against the chimney. He is also someone whose story has not been told, certainly not in this part of the world, and possibly never. He served in two wars, fought for the freedom of his country, and was lost on the Eastern Front of the Second World War. It is a strange paradox that the awful upheavals of that great conflict also led my mother and grandmother to leave their homeland and eventually settle in New Zealand, where my mother and father met. I owe my life to the same set of circumstances that caused my grandfather’s death. Latvia, where my mother and both her parents were born, is one of the Baltic States that now represent the easternmost extent of the European Union. Although today it is once again an independent republic, for most of its history Latvia was ruled by larger powers. Only in the aftermath of the First World War did it gain independence from the Russians. The two decades from 1920 to 1940 saw a proud flourishing of national and cultural identity that was crushed by the Second World War. In June 1940 the Soviet Union invaded and instigated the ‘Year of Terror’ in which tens of thousands were arrested, executed or sent to Siberia to perish or lost their minds. In August 1941, the Soviets were displaced by the Germans, who brought their own terror in the shape of the Holocaust. By the beginning of 1944, the Nazis were being driven back. The capital, Rīga, fell again to the Soviets on 13 October 1944 and Latvia was forcibly incorporated into the Soviet Union. The years that followed were a period of brutal repression. Surveillance, disappearances, alienation of private property, forced collectivisation of agriculture, and mass deportations left a deep wound in the national psyche. My mother knew almost nothing about her father. She was a small child when he was conscripted into the German army that occupied Latvia. With their defeat becoming inevitable, the Germans had resorted to bolstering their forces with Latvian ‘volunteers.’ ‘After he was conscripted,’ my mother recalled, ‘my father was interned for a while in Rīga before being transported somewhere. Nanny visited him during that time, and took him food and other things.’ After that there were a couple of letters, and then silence. As the Soviet army advanced towards Rīga in the latter half of 1944, my grandmother took her two daughters and fled, along with tens of thousands of other Latvians escaping the Communist terror. By the time Rīga was taken by the Russians, my mother, grandmother and aunt were in a refugee camp in Germany. My grandfather, missing on the eastern front, was never found. My grandmother lost all contact with the family she left behind. She was afraid they would be persecuted if she tried to get in touch. Under Stalinism, simply receiving a letter from a relative in the West could lead to arrest and interrogation by the secret police. My grandmother never spoke of her first husband. All we knew were his name and occupation. Aleksejs Ulachovičs had been a shoemaker, and my mother vaguely remembered the shop he kept downstairs in the building where they lived. Just two photographs of him survived. One is a creased, postage-stamp sized fragment cut from a larger picture. The other always puzzled me. It shows a group of men in military uniform posed in a studio. Seated on the ground in front, also in uniform, is a boy who can scarcely be 16. ‘That’s my father there,’ Mum always said, but I had my doubts. He seemed far too young for this to have been a photograph from the Second World War. My mother could offer no other explanation. ‘Rīga was bombed. All the records were destroyed,’ my mother told me, when as a teenager I tried to construct a family tree. The past had been lost. There was nothing more to connect us with our roots than the handful of photographs my grandmother Tatjana had saved. But my mother was wrong. ‘The Nazis who occupied Latvia, and the Communists who followed them, were both totalitarian regimes,’ said Antra Celmins, the genealogist I contacted when I first visited Rīga in 2016. ‘They wanted information on their citizens and worked hard to preserve records, not destroy them.’ Latvia regained independence in 1991 and in today’s post-Soviet era of openness and digitisation of archives, that information is now available to the children and grandchildren of Latvian émigrés keen to reclaim their heritage. Antra went on, ‘I’ve found your grandfather’s passport file.’ This was what I wanted my mother to see when I took her back to Latvia in 2017. There, safeguarded in the national archives was the passport her father had held in the 1920s. Technically it was an ‘identity certificate’ issued to stateless persons. ‘Of Russian origin, having no other nationality,’ it said, but the space for ‘place of birth’ was left blank. On the front page was stamped: ‘Anulēts, 1930. g. 12 XII,’ – cancelled, 12 December 1930. The next document explained why. At the end of 1930 my grandfather was granted Latvian citizenship for having served in the Latvian Army – almost certainly during the 1918–1920 War of Independence, the chaotic conflict in which Latvian nationalists repulsed the invading Bolsheviks, while simultaneously struggling to displace the occupying Germans. As a Latvian citizen he no longer needed a stateless person’s identity certificate. The story became clearer when I visited the Latvian War Museum. There I showed one of the historians the photograph of the soldiers. ‘That’s one of our pictures, taken around 1920. Those are Latvian Army uniforms,’ he said. The museum had commissioned photographs to commemorate those who fought for Latvia’s independence. Later he sent me an e-mail: ‘We found a certain “Aleksejs Vlachovics” in our World War II records. It was quite common for Germans to misspell the surnames of Latvian soldiers. He was born in Rīga on June 2, 1906. On February 24, 1944 he was enlisted into the 4th Company of the 3rd Border Guard Regiment.’ I thought again of the passport in the archives, issued nearly twenty years earlier. I could imagine why my 18-year-old grandmother might have fallen for the poised, rakish ex-soldier in cap and cravat who stares defiantly from the photograph inside. Suddenly it made sense. The boy in military uniform was indeed my grandfather. In 1920, when the picture was taken, he was 14: a teenage soldier in the War of Independence. He must have lied about his age to join up. That was confirmed back at the archives, where we also found his citizenship file. There, handwritten in the pre-Revolutionary Russian script of a priest from the Orthodox church where he was baptised, was his birth certificate. It had been issued in 1913, when Latvia was still part of the Russian Empire. He was indeed born in Rīga, where his father had been a warden at the prison. His mother was from Byelorussia. His date of birth was given as 20 May 1906. Russia used the old Julian calendar until 1918: adding twelve days takes us to 2 June, the birthdate given by the military records. I was curious to find out more. In 2018, my third trip to Rīga, I returned to the War Museum to see for myself the handwritten register recording Aleksejs’ enlistment. There, one of the historians showed me a four-volume Latvian military history, written by post-world War II émigrés and published in Sweden in 1976 when the iron grip of the USSR was still unrelenting. At the beginning of July 1944, my grandfather’s regiment was sent to the region of Krasnoe in what is now Belarus, about 50 km northwest of Minsk. Between the 10th and 18th of July the regiment recorded the deaths of one officer and ten soldiers. Twenty officers and 785 soldiers were missing, ‘lost without news.’ The report was confirmed in an e-mail from the German Army’s Centre for Military History and Social Sciences: ‘On the 16th July 1944 this division was annihilated in a fight with Soviet troops.’

Tears came to my eyes when finally, with the aid of my dictionary, I translated that last sentence: 785 soldiers lost without news. What chaos. What carnage. We shall remember them.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorA photographer, oral historian, writer, and general fan of arcane technology Archives

April 2020

Categories

All

Blog links

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed